It's Time To Rethink Shoe-Horning Cell And Gene Therapies Into A Pharma Business

By Dr. Sanjay Srivastava, Managing Director, Life Sciences IX.0/SCO Practice; Dr. Boris Bogdan, Managing Director — Global Lead Precision Oncology and PHC; and Dr. Sandra Dietschy-Kuenzle, Senior Principal, Accenture Life Sciences

Companies have more options to incorporate cell and gene therapies (CGT) into their operations.

By Dr. Sanjay Srivastava, Managing Director, Life Sciences IX.0/SCO Practice; Dr. Boris Bogdan, Managing Director — Global Lead Precision Oncology and PHC; and Dr. Sandra Dietschy-Kuenzle, Senior Principal, Accenture Life Sciences

Cell and gene therapies are revolutionizing medicine. They often offer superior treatment options for life-threatening illnesses, and in some cases, have the potential to cure diseases altogether. The sustained outcomes CGT offer are a function of their unique approach. Instead of treating symptoms of a disease, CGT aim to treat its underlying causes by actually modifying cells and genes.

Despite its relative novelty as a treatment, we have already seen several CGT successes. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 17 CGT drugs so far, including two advanced cell therapies to cure leukemia and lymphoma.[1] This success has spurred a two-fold increase in new clinical trials per year over the last three years.[2]

Today, with more than 2,000 ongoing clinical trials covering more than 10 therapeutic areas, CGT are creating significant ripple effects across the social, clinical, and economic spectrum. The FDA has indicated that it expects to approve 10 to 20 new CGT between now and 2025.[3] These new product launches are expected to grow the market value of CGT exponentially—from $1.1 billion in 2019 to more than $30 billion by 2025.[4] Investments in CGT have also risen, with companies active in CGT and other regenerative medicines raising nearly $10 billion in 2019.[5]

Today, clinical-stage, pre-commercial biotech companies are conducting most of the clinical activity in CGT with large biopharma companies administering a relatively small share of studies.

However, large biopharma recognizes a sizable growth opportunity and has made it a priority to invest into CGT. Because most of the CGT clinical trials are sponsored by smaller biotech companies, to enter the space, acquisitions and collaborations have become an attractive option for biopharma. We are witnessing a significant uptick in CGT MA activity; major biopharma companies are increasingly focusing on pursuing inorganic growth strategies to enhance their product portfolio in the CGT space. Some of the larger acquisitions in recent years include Roche’s purchase of Spark Therapeutics for $4.3 billion in 2019,[6] Celgene’s acquisition of Juno for $9 billion in 2018[7], Novartis’ acquisition of Avexis for $8.9 billion in 2018[8] and Gilead’s acquisition of Kite for $11.9 billion in 2017.[9]

Exploring the Business Models

Big pharma’s intensifying interest in the CGT arena also presents many challenges. In particular, today’s life sciences industry’s drug development and commercialization business model is designed largely around small molecules and biologics.

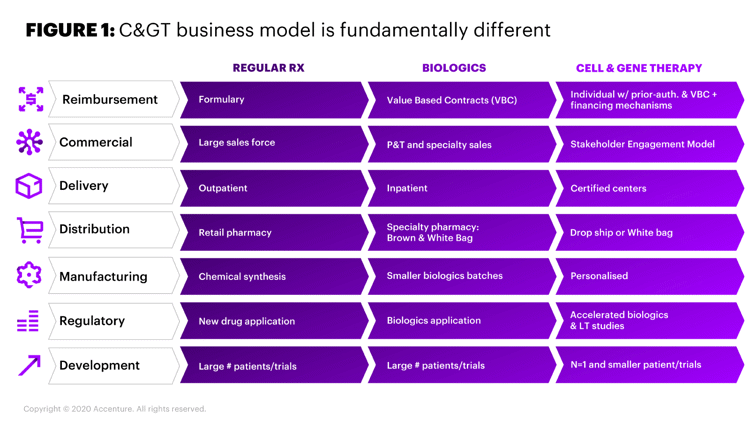

Additionally, the value chain for CGT is different than traditional pharma. The technical complexity of gene therapy, the need for speed and the differences between gene therapy and traditional therapies with respect to development, manufacturing, and commercialization require new, specialized capabilities (Figure 1). These therapies don’t fit easily into big pharma’s current ways of working, budgeting and decision-making. Efficient development and commercialization of CGT requires embracing a shift in the traditional biopharmaceutical business model.

Figure 1. CGT Business Model is Fundamentally Different

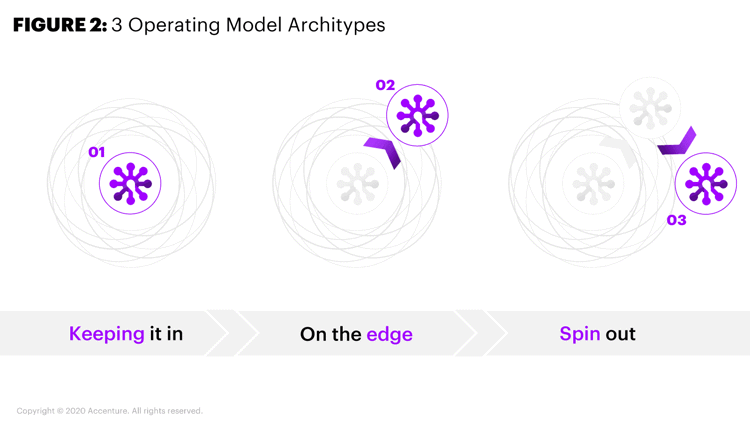

Because of the vastly different development and commercialization models, leaders within big biopharmaceutical companies are struggling with the three operating model archetypes when managing CGT operations: Integrate them into the larger pharma operations; keep them on the edge of the core operations; or spin them out and set up a completely separate, vertically-integrated business unit (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Three Operating Model Archetypes

The industry has experimented with each of the three models of organizing and operating a CGT business. Several companies have tried the various approaches to incorporating CGT — shoe-horning gene therapies into their current model, keeping core components of CGT operations on the edge or spinning them out completely.

Shoehorning CGT operations into the traditional model can help companies achieve several common operational goals, often from combined operations, enabling core functions such as finance and HR, for example. Without recognizing and adjusting for fundamental differences in R&D, commercial, supply chain and manufacturing, fully integrating the operations often leads to significant inefficiencies, however.

Keeping the operations on the edge seems attractive because it can enable a rich exchange of new knowledge within and across the edge and drive rapid development of CGT assets. But unless a company folds select traditional operations into the edge operations, it will fail to take full advantage of the benefits that CGT operations offer.

Because CGT foster experimentation and innovation opportunities, some big pharma companies believe that keeping them as a separate business is the best way to adapt to CGT’s shifting nuances and changing needs. However, this approach offers no opportunities to realize synergies and capture value. Specifically, it fails to provide fiscal and operational value, which would often be required to justify costly acquisitions.

Over the long-term, companies must adapt to make their business models more efficient, shorten time-to-market and lower operational costs. The three models are neither mutually exclusive nor static. Under the right scenario—and with optimized capability distribution—any of the three can drive innovation and be a source of business growth for CGT manufacturers.

How Do We Make a Model Work?

So, how can biopharma companies ensure that they forge the link between innovative, game-changing CGT development and commercial operations with the traditional product organization?

When there is more than one CGT asset in the pipeline, integrating a CGT operation into a pharmaceutical company comes with complications and requires nuance. We believe there is a sweet spot for post-merger success between a fully integrated entity and two separate entities. It is not an either/or decision and raises the question not whether if the businesses should integrate, but rather a question of where—specifically, where along the value chain. We believe there are two scenarios in which an acquiring company and its new CGT should integrate: When there are lessons to learn from the CGT; and when there are strengths to capture between the two entities. Within each of these two scenarios there are specific points in the value chain that will most effectively integrate the businesses and maximize the benefits a company can reap from the acquisition.

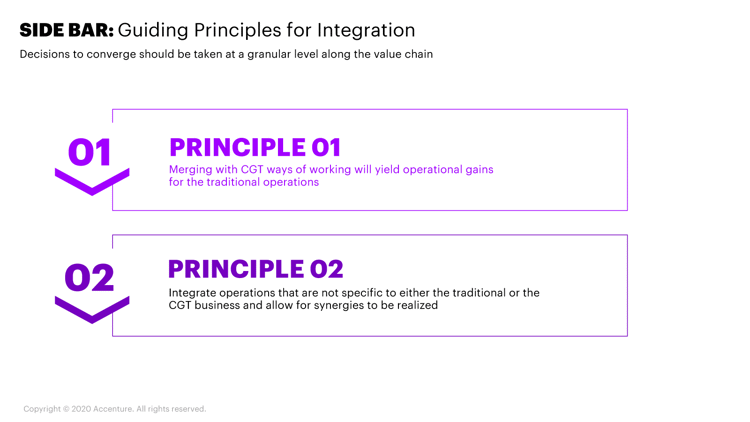

Guiding Principles for Integration

The first guiding principle to consider when deciding whether to integrate or not requires exploring what the traditional business can learn from the CGT model. In certain cases, it might be appropriate for the traditional model to consider the practices of the CGT operating model. The acquiring business may need to recalibrate its operating model when it can achieve higher performance levels by integrating and adopting the capabilities to manage CGT operations.

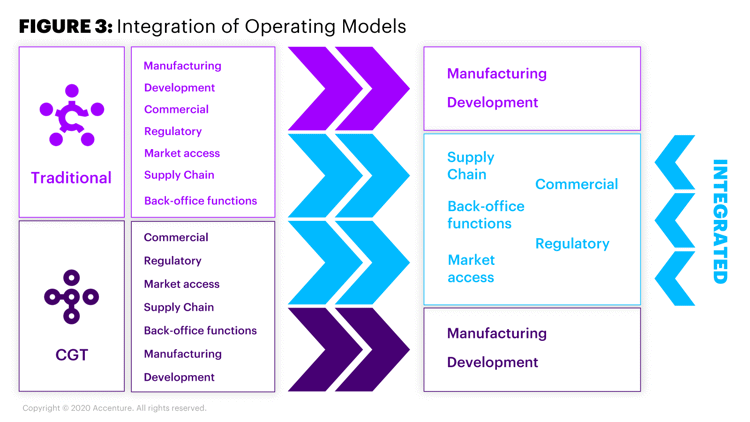

We’ve identified three critical points on the value chain that are ripe targets for integration where the acquiring company has an obvious opportunity to learn and evolve (Figure 3):

- Supply chain. Traditional supply chain operations can benefit from the patient-centricity and agility of the CGT model. Traditional pharmaceutical companies have aspired to adopt a truly agile and demand-driven model, but many falter on the execution. By contrast, CGT by nature is demand-driven and dynamic and requires end-to-end transparency in operations. We believe its influence on traditional pharmaceutical operations can be powerful.

- Commercial. We see potential for acquiring businesses to open the aperture and expand the current aspects of biopharma’s commercial excellence on “where to play” and “how to play.” CGT skews to a broader patient- and stakeholder-centric commercial experience that tracks the patient journey, consults rather than sells, and acts as an advisor and partner with physicians rather than acting as a transactional representative and drug supplier. We believe that traditional pharmaceutical companies have great potential to better serve customers by adopting this commercial positioning.

- Market access. We foresee conventional business’s market access and reimbursement strategies becoming increasingly patient- and healthcare provider-centered and outcome-based where pricing and drug access are concerned. And CGT companies already operate with outcome-based pricing, annuity payments over several years, and financial and logistics support programs. Therefore, we believe that by combining the two market access business operations, the influence of the CGT can help elevate the traditional business to better place the products in the marketplace that improve therapy access to the patients.

Figure 3. Integration of Operating Models

The second guiding principle to explore has to do with whether there are transferrable capabilities not specific to CGT that can be integrated to create cooperative efforts beyond the specifics of CGT. If there are indeed strengths to capture, integration is a must. We believe the areas in the value chain that will lead to the greatest benefit from such combinations are regulatory and enabling functions such as HR, finance and legal.

Generally, enabling functions offers countless opportunities to integrate and transfer skills. In our view, this makes integrating enabling functions wherever possible an obvious advantage companies should seize. The regulatory function for both traditional pharmaceutical companies and CGT have striking similarities—among them, their requirement for high levels of regulatory intelligence and emphasis on patient safety. Fully integrating the regulatory functions of both businesses offers huge opportunities to combine forces and present a single face to the health authorities, while adopting a differentiating strategy to manage mixed portfolio.

Integration is Not Always the Best Option

While there are many opportunities for integration, not all acquisitions will necessarily succeed from integrating. For example, when there is a single CGT asset in development, it is best to keep its development operations on the edge. With multiple assets, sometimes there will not be a clear path for the traditional business to evolve based on lessons learned from the model of the CGT business. In that case, we recommend operating separately. While there are many points on the value chain that benefit with integration, not all will gain value.

Even if a majority of the acquiring company and the CGT integrate, we believe that there are two important functions that are best managed separately: manufacturing and research and development (R&D). Both are extremely different for traditional pharmaceuticals and CGT, and both operate and optimize under different metrics of success—combining them could actually cause great harm to the business.

For the manufacturing function, cost and efficiency are typically features that optimize a traditional pharmaceutical company. On the other hand, reach-to-patient, logistics and network footprint are typically the optimizing features of CGT. Manufacturing should be a dedicated and separate operations to properly optimize based on success metrics.

Similarly, R&D functions should be kept separate as centers of excellence, as the target identification and validation processes for CGT R&D are very different than conventional drug discovery. Additionally, clinical operations require different set of capabilities to manage clinical sites and the enabling infrastructure to manage clinical data and supplies.

Now is the time for large biopharma to go beyond structure and redefine their entire operating model, laying out the blueprint for how core, innovative and enabling capabilities are distributed and organized to drive operational efficiency across the two operating paradigms.

We believe companies will have to embrace the idea of multi-modal operating models for specific elements across the value delivery chain. In those cases, all the pieces of the multi-modal operating model—structure, governance, essential behaviors as well as the way people, processes and technology integrate to deliver capabilities—must be designed explicitly to support the overall model that supports a mixed portfolio of assets.

This article is adapted from a forthcoming study by Accenture.

The authors would like to thank Benjamin Ferrara for his support to write this article.

[1] https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/approved-cellular-and-gene-therapy-products

[4] Evaluate Pharma

[5] https://alliancerm.org/press-release/the-alliance-for-regenerative-medicine-releases-2019-annual-report-and-sector-year-in-review/

[7] https://www.celgene.com/newsroom/cellular-immunotherapies/celgene-corporation-to-acquire-juno-therapeutics-inc/