Could Chicken Wisdom Help Cell Therapies Spread Wings?

By Kat Kozyrytska

In a recent discussion with Life Science Connect’s own Ray Dogum, who has been covering federated learning/decentralized AI in pharma/biotech (TuneLab, OpenFold3), he asked me why would someone engage in a precompetitive collaboration and share their data?

The answer I gave is that some questions are too complex to answer for a single company.

Let’s take novel drug target identification, a very expensive and lengthy endeavor, which arguably is the bottleneck in advancing medicine. I had the immense pleasure to have been employed at Olink Proteomics now part of Thermo Fisher Scientific, when the Pharma Proteomics Project was conceived by Chris Whelan, then of Biogen. It is one of the most profound precompetitive collaborative projects where 14 — competing — companies have pitched in resources for proteomic profiling of the UK Biobank sample cohort in order to unlock new drug targets across indications. By collaborating, these companies were able to discover over 10,500 new potential targets, — which will hopefully lead to new therapies for more patients sooner.

When I took a deep dive into the challenges the field of cell therapies has been facing, I came up with what I thought was a most natural idea: a precompetitive collaboration to better understand manufacturability. This is a perfect question to address collaboratively: it’s poorly understood, too complex and expensive for any one company to tackle, the amount of data each company holds is limited, — and the outcomes would be tremendous for patients. Moreover, we had already seen that manufacturing methodology — eventually — converged for traditional biologics and that cross-sector analyses had helped with developability assessment . The collaboration seemed to be a no-brainer. I have since met a number of professionals (mostly those who have worked across modalities) who had also considered some shape of a collaboration to solve cell therapy’s problems. It seemed so obvious. I pitched a collaborative approach over and over. There were a few resounding yesses, some nods in the audience, but no, I did not have hundreds of companies lining up to join the collaboration.

This led me to ask the question: We have succeeded as a species, again and again, through collaboration. When and why do we make the choice not to collaborate? I am a scientist by training, so I approached this with a literature search and came upon multilevel selection, which has been studied extensively in the context of evolution.

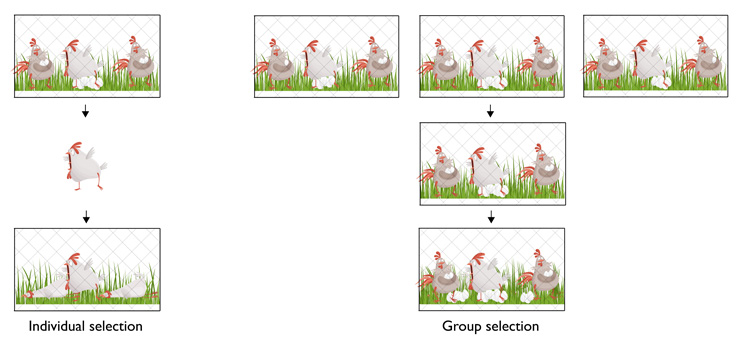

A key experiment in multilevel selection was published in 2007 by Bill Muir of Purdue. In short, the experimental objective was to select chickens with the highest egg-laying productivity. The experimental setup compared individual selection against group selection. In individual selection, the highest -egg-producing chickens from each cage were chosen and propagated. In group selection, the highest-egg-producing cages were chosen and propagated. After some rounds, contrary to what some may expect, individual selection led to aggressive chickens that not only didn’t perform well with egg production but also pecked each other to death. Group selection, on the other hand, led to better egg production overall.

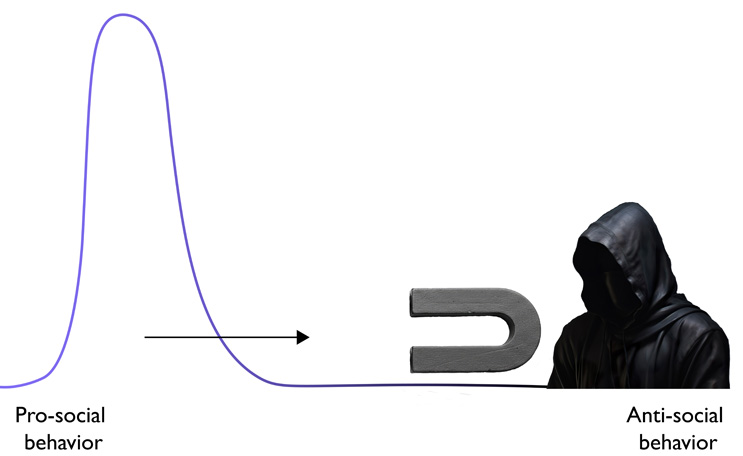

Translating this to the business world (as many others have done), self-focused, competitive, and predatory behavior gets you a win within the group. The term used to describe individuals exhibiting these behaviors is “dark personalities,” and their behaviors as they contort the organization to serve their interests can be subtle and hard to detect (also studied extensively, along with their devastating effects on organizations; some of the thought leaders to read are Karen Mitchell (Kalmor Institute), Baloch et al. (1972), and Cynthia Mathieu (UQTR)).

Adapted from "Why 'Humans' Are Better Than We Think"

However, when it comes to competition between groups, what leads to success is within-group cooperation and alignment toward shared goals. In the words of David Sloan Wilson, Prof. Emeritus of Biological Sciences and Anthropology at Binghamton University, “selfishness beats altruism within groups, altruistic groups beat selfish groups.”

Consistently, in cell therapy, competition has been between cell therapy companies. However, looking at the landscape today, I would argue that competition for cell therapies is against ADCs, bi/tri/multi-specifics, and on and on — sectors that are yes, more mature, but also have been much more collaborative and open to information sharing (e.g., via NIST, BioMADE, the Enabling Technologies Consortium, and the Digital Twin Consortium). In this “group selection,” cell therapies are not winning.

Working in the field of cell therapies, I met an overwhelming number of people who are dedicated to improving patient lives — more than I had encountered elsewhere. They live and breathe to bring curative treatments to patients. Yet, cell therapy is also the most reserved field when it comes to idea sharing that I have encountered in my 18 years in academia and industry.

How can we reconcile these?

Lack of clarity as to where the IP lies (the unfortunate “process is the product” mindset) is often cited. But we’ve innovated previously; I am sure there were some gray areas, and yet we found ways to cooperate and share information. Moreover, such a large fraction of the cell therapy sector has a recent academic past, which should only lead to more open discussions.

Nate Hagens of the Institute for the Study of Energy and Our Future makes an excellent argument that while we are naturally highly cooperative and altruistic, a small fraction (Karen Mitchell estimates this at 10%) of the population is not. Uncooperative behaviors of this fraction, when unpunished, sway the rest of the group toward un-cooperation and lead to, among other things, less idea sharing. It’s still early on this, but altruistic professions, such as healthcare (I will count pharma/biotech here), seem to be more susceptible to manipulation because as fundamentally good, moral people these professionals assume the same about others, fail to question motivations, and can end up — unknowingly — a part of someone else’s plan.

Adapted from "Why 'Humans' Are Better Than We Think"

In their publicity, novelty, and abundant early investments, did the field of cell therapies inadvertently attract individuals whose focus was somewhere other than on improving lives of patients? Did their uncooperative behaviors shift the overall landscape of idea sharing? More importantly, how can cell therapies still get back to cooperation and collaboration to compete better in “group selection”? How can we ensure that the next innovative modality follows a different path and we bring therapies to patients faster?

We’ve been looking to AI for novel insights, hypotheses, and experimental designs. A recent paper shows the power of AI to generate hypotheses the leading scientists claim to not have been able to come up with themselves — and then following up with well-planned experiments. But the power of AI is in access to information. Imagine what it could do for cell therapies if we let it — in a privacy-preserving way — look at the sector’s cell therapy data. Could we have the answers about what markers to use for starting material profiling, which technology to use for each cell type, which cell type to use for which indication in six months?

By collaborating, can we find a faster path to optimal infrastructure? Reasonable pricing? Reimbursement model?

With the next exciting innovation of in vivo cell therapies, there is — once again — great potential in the technology but a lot of complexity and unanswered questions: dosing, targeting, monitoring, and so on. Some of the risks posed by these challenges can be mitigated by applying insights from ex vivo — for example, by leveraging learnings from ex vivo starting material characterization to refine patient eligibility criteria for clinical trials for in vivo. Whether ex vivo therapies will persist or not, a collaborative approach can still help in vivo therapies — and serve the needs of patients.

We have made it this far as a species by being predominantly altruistic and prioritizing the common good. A high-potential, high-complexity area of cell therapy gives us another chance to demonstrate our built-in, proven-by-evolution, winning ability to collaborate and cooperate. Let’s do it.

About The Author:

Kat Kozyrytska is a technology consultant who provides services to AI developers helping them commercialize and grow market adoption and to biotech and pharma companies helping them mitigate AI deployment risks. She holds an S.B. in biology from MIT and an M.Sc. in neuroscience from Stanford University.

Kat Kozyrytska is a technology consultant who provides services to AI developers helping them commercialize and grow market adoption and to biotech and pharma companies helping them mitigate AI deployment risks. She holds an S.B. in biology from MIT and an M.Sc. in neuroscience from Stanford University.