4 Centralized Comparator Sourcing Models To Fortify Supply Chains

By Giuseppe Coppola and Pelin Bilgin — Novartis, and Simon Pannatier — a-connect

Comparator supply decisions are becoming increasingly critical to the success of clinical trials, yet they are often made too late. As study designs become more complex and start-up timelines tighten, it’s essential to incorporate comparator considerations early, giving them a seat at the study table from the pre-feasibility phase onward.

Our team at Novartis explored this issue and identified four viable models for centralized sourcing of comparators to support our internal pipeline. The broader set of models and the structured approach behind them may help other drug sponsors navigate the trade-offs inherent in sourcing strategies and avoid the kinds of supply issues that can delay, disrupt, or even shut down clinical trials.

The Missing Pieces That Can Break The Puzzle

In any clinical trial, all eyes are on the reliability, safety, and efficacy of the investigational medicinal product (IMP). Comparator drugs, however, often receive far less attention. Yet when they fail, the entire trial can teeter on the edge. A delayed shipment, a quality lapse from a local vendor, or a misstep in regulatory handling can trigger stockouts, force a trial suspension, and erode trust in the sponsor’s ability to run a compliant and reliable trial. What begins as an overlooked operational detail can quickly become a full-blown clinical crisis.

In many organizations, the supply of comparators, open label medication, and some non-IMPs is still handled locally. For example, in a global study with sites in France and India, clinical teams might reach out to different local vendors for supply. This approach may be pragmatic in the short term but it comes with significant downsides:

- Vendors may lack GMP expertise, putting patients and trial continuity at risk.

- Decentralized sourcing often leads to shortages, outages, and excess waste.

- Clinical teams are pulled away from their core mission of running the trial.

- Fragmented, country-by-country processes reduce global visibility and increase the risk of counterfeit products reaching patients.

Despite the risks of decentralized sourcing, few alternative models exist as practical benchmarks in the industry. To help organizations move beyond ad-hoc local approaches, a deconstruction of sourcing and supply operating models reveals four distinctive alternatives that can realistically be applied.

Four Models To Replace Local Sourcing

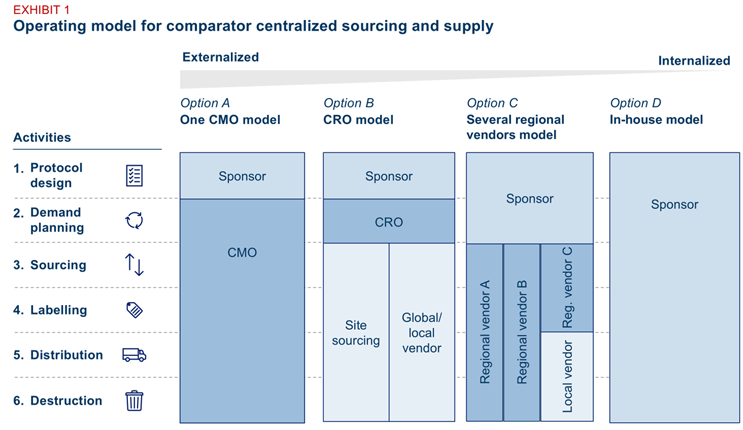

Our team developed four operating models for centralized supply of comparators, open label medication, and some non-IMPs. Each one varies by two key factors:

- The level of outsourcing across the clinical supply value chain

- The degree of intermediation between the sponsor and trial sites

Exhibit 1: Comparator supply operating models

All four models assume that:

- The sponsor retains trial accountabilities for protocol design, regulatory submissions, and any engagement activities with health authorities and ethics committees.

- Downstream supply activities are centralized and often outsourced. Tasks such as ordering, labeling, packaging, releasing, and distribution are consolidated into a single workflow. In most cases, these activities are executed by third-party partners.

- Site-level sourcing — the ability to source a drug directly from the site pharmacy — remains a valid alternative. In certain cases, such as urgent or protocol-specific supply needs, site-level sourcing can complement the centralized model.

- Scale is essential to make outsourcing viable. Outsourcing delivers efficiency only when applied across a sufficient number of studies or drugs. A certain baseline of volume is needed to justify the setup and oversight costs.

Choosing The Right Model: Trade-Offs And Lessons

Each model reflects a different balance of control, flexibility, and complexity. The right choice depends on how much ownership the sponsor wants to retain, how much variability exists across studies, and how prepared the organization is to coordinate across partners. The following breakdown outlines the core characteristics, strengths, and trade-offs of each option.

1. CMO-led model

A single global contract manufacturing organization (CMO) handles all downstream activities (demand planning, sourcing, labeling, distribution, returns, and packaging), while keeping the protocol design responsibility with the sponsor. This simplifies oversight, speeds issue resolution, and minimizes coordination. However, it also concentrates risk in one vendor and may reduce access to regional supply strengths.

2. CRO-led model

A contract research organization (CRO) serves as the primary partner to the sponsor and coordinates supply through external sources. However, most CROs lack the GMP capabilities required to handle drug supply directly. As a result, they typically subcontract to a CMO, which in turn manages regional vendors. This structure brings sourcing agility and market intelligence but also increases complexity and may reduce visibility between the sponsor and end supplier.

3. Regional vendor model

This option allows for a strong regional footprint (e.g., wholesalers, depot, site, etc.), regulatory know-how, and local agility (e.g., importer of records capabilities). But it also increases complexity: sponsors must manage multiple vendors, contracts, and interfaces.

4. In-house model

Full internal ownership allows the sponsor organization to leverage internal systems, teams, and processes. This enables tighter control over quality, timelines, and compliance. It also simplifies governance by eliminating third-party coordination, but it demands significant internal resources, requires breaking down functional siloes, and lacks flexibility in variable or niche supply chains.

How To Select The Right Model For Your Organization

There is no universally “best” operating model — only the one that fits your organization’s goals, supply landscape, trial portfolio, and resource capacity. Each model comes with trade-offs in control, complexity, and coordination effort. For example, a regional vendor model may offer strong local coverage but requires more internal resources to manage multiple partners across markets.

Start by answering four key questions:

1. What Are You Optimizing For?

Are you solving for GMP compliance, forecast accuracy, distribution reach, or operational simplicity? Define your objectives clearly before comparing models.

Exhibit 2: Design principles

Many organizations default to what’s familiar — continuing long-standing vendor contracts or replicating historical setups. But legacy arrangements often reflect convenience, not optimization. Instead, define a clear set of design principles that reflect your current objectives — whether it’s risk mitigation, faster delivery, or global standardization. Then translate those principles into objective assessment criteria and apply them consistently across all model options. This will help separate strategic fit from organizational habit.

2. Which Drugs Are In Scope And Which Are Not?

Not every drug is suited for a centralized sourcing model. Some are better sourced from the site pharmacy due to ease of access, increased eligible patient population, variability, or regulatory complexity. For example, rescue medications are needed in small quantities, urgently and often unpredictably, making site-level sourcing more practical.

Begin with the study protocol: classify the drug as an IMP, auxiliary medicinal product (AxMP), or concomitant medication. Then, assess key supply attributes — volume, ability to forecast, shelf life, urgency, and lead time.

Centralized sourcing tends to deliver the greatest value for high-volume, predictable drugs that are critical to the trial’s success. Conversely, local sourcing may be more suitable for drugs with investigator-specific variability, short shelf life, or low usage frequency.

Once the preferred supply model is identified for each drug type, explicitly define the central sourcing scope. A helpful approach is to start by exclusion — listing products that cannot be sourced centrally — and refining the scope from there.

However, drug characteristics alone don’t determine feasibility. Site-level realities and market-specific constraints must also be factored in. National regulations, site pharmacy capabilities, and local availability may influence whether a drug is suitable for central supply. For instance, a comparator drug may be well suited for centralization in theory but still requires local sourcing in countries with restrictive regulatory frameworks.

As organizations gain experience and scale centralized supply across more studies, the sourcing scope will naturally evolve, broadening as capabilities mature and complexity becomes more manageable.

3. What Is Your Current Supply Baseline?

Before selecting a centralized model, organizations need a clear understanding of their current supply setup and how much change they can realistically absorb. Two dimensions matter most: how supply information is managed and how ready the organization is to transfer processes to external partners.

First, centralization requires a shift in how information flows. In many companies, key inputs — such as FSIV (first site initiation visit) dates, country-specific requirements, or site lists — are managed at the local level. To operate a centralized model, this information must be consolidated, standardized, and visible at the global level. Without this foundation, even the best-designed operating model will underperform.

Second, outsourcing introduces a new layer of coordination, one that demands tight alignment across functions. When sourcing, packaging, labeling, release, or distribution activities are handed to a third party, internal teams must work hand in hand with external partners. For example, if an amendment is submitted to health authorities, the regulatory team must promptly inform the clinical supply function so that the vendor knows when to proceed with procurement or release.

These changes stretch the organization’s operating muscle. Siloed functions, unclear accountabilities, or manual workarounds can quickly become bottlenecks.

Assess whether your organization is equipped to centralize data and delegate execution. Do you have global visibility on trial timelines and supply needs? Are your internal processes well documented and standardized? Have cross-functional teams worked with third parties before?

As a starting point, identify the critical supply-related processes — such as submission tracking, release readiness, and country start-up — and map the teams who contribute to them. Engaging those teams early is essential: they hold the operational knowledge, and their alignment will make or break your transition.

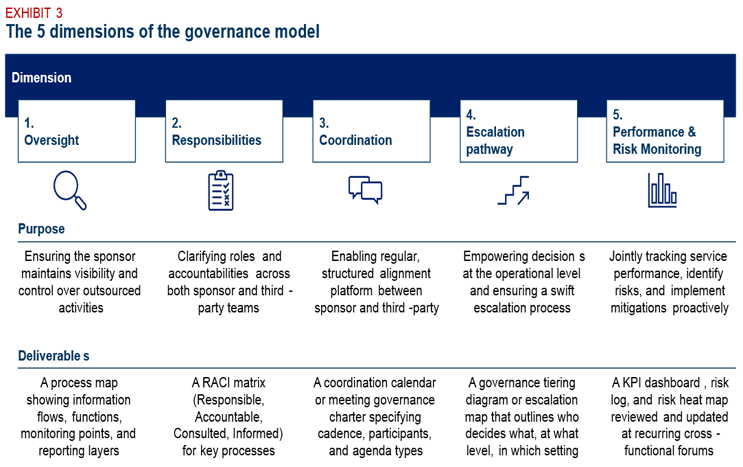

4. What Governance Structure Is Needed?

Outsourcing comparator supply shifts operational responsibility to a third party, but the sponsor remains fully accountable for compliance, quality, and trial continuity. This duality makes governance essential. A well-designed governance model complements contractual agreements by defining how decisions are made, how issues are resolved, and how alignment is maintained day to day.

Governance is not a substitute for contracts or incentives; it's an operational overlay. While the master service agreement (MSA) defines roles, deliverables, and commercial terms, governance defines how people interact: how often they meet, what they escalate, and how accountability is preserved across organizational boundaries.

We recommend designing your governance around five key dimensions, each of them playing a distinct role — and each should result in a specific operational output. The table below outlines both the purpose and the expected deliverable for each of the five dimensions.

Exhibit 3: The five dimensions of the governance model

Turning Comparator Supply Into A Strategic Advantage

GMP compliance gaps, sourcing inefficiencies, and supply fragmentation can threaten trial integrity and delay timelines. A centralized model offers a path to mitigate these risks, but its success hinges on choosing a model that fits your organization’s footprint, capabilities, trial portfolio, and priorities.

Rather than defaulting to legacy practices, organizations should take a structured approach:

- Define your objectives clearly, whether it is compliance, continuity, or cost.

- Establish a baseline across systems, teams, and current supply models.

- Evaluate which drugs and processes are in scope, and why.

- Pilot selected models across a representative set of protocols.

When executed with the right scope, governance, and internal alignment, centralizing comparator supply can turn clinical operations from a potential bottleneck into a strategic enabler of high-quality, risk-resilient trials. It also enhances the sponsor’s ability to anticipate and absorb external shocks — from local market disruptions to supplier variability — by building consistency and control into the sourcing model.

Ultimately, centralizing comparator supply puts the missing pieces into place, not just to streamline operations but to turn patient trust into trial integrity and trial integrity into real-world outcomes.

About The Authors:

Giuseppe Coppola is Head of Global Clinical Supply Operations at Novartis where he has worked since 2014. He received a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Naples Federico II.

Giuseppe Coppola is Head of Global Clinical Supply Operations at Novartis where he has worked since 2014. He received a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Naples Federico II.

Pelin Bilgin is Team Head of Comparator Management, Global Clinical Supply, at Novartis. Previously, she worked at Bayer where she held various roles in Operations and Supply Chain Management. She received a B.Sc. in pharmacy at Istanbul University.

Pelin Bilgin is Team Head of Comparator Management, Global Clinical Supply, at Novartis. Previously, she worked at Bayer where she held various roles in Operations and Supply Chain Management. She received a B.Sc. in pharmacy at Istanbul University.

Simon Pannatier is a Project Manager at a-connect, a global consulting group. Previously, he worked at Boston Consulting Group. He received a master’s degree in business from ESCP Business School and an MBA from INSEAD.

Simon Pannatier is a Project Manager at a-connect, a global consulting group. Previously, he worked at Boston Consulting Group. He received a master’s degree in business from ESCP Business School and an MBA from INSEAD.