Cell & Gene Therapies: Avoid This Common Pitfall In Supply Chain Planning

A conversation with Donnie Beers and Ike Young, members of BioPhorum

The rapid development of new cell and gene therapies typically allocates most resources to scientifically defining and implementing the therapy under development. Consequently, other critical disciplines — such as supply chain management, operations, and procurement — often take a backseat until the later stages of the product life cycle. By this point, sourcing decisions have already been locked-in during the initial development phase and changes to materials, contracts, and terms and agreements are almost impossible.

We asked two BioPhorum members — Ike Young, senior director of GxP procurement & supplier management at Sangamo Therapeutics; and Donnie Beers, applications leader, cell and gene therapy at Entegris, Inc. — some questions to explore the challenges and BioPhorum’s proposed organizational model solution in more detail. They provide recommendations for relevant supply chain processes and how to integrate them earlier into the development cycle to ensure robust and cost-effective sustainable supply chains to support product growth.

Can you provide some examples where deferring supply chain activities to later stages in the product life cycle led to challenges?

There are many examples from our years of experience. One was the choice in development to use a simple phosphate salt that worked well in the cell culture process but was later discovered to have never been intended for pharmaceutical manufacturing and had no compendial monograph. When black specks were found by the quality group, the supplier said to stop using the salt for such processing as it wasn’t made for that. But it was very late to start seeking alternatives.

Another example is the selection of a manufacturer that claimed to have a remarkable technology for cell sorting. It worked very well, but when the quality group was catching up and sought standard quality documentation (Certificate of Analysis, Certificate of Conformance, etc.), there was none to be had. The manufacturer was simply dabbling in the biotech business — their core was a high-revenue-generating optics business, and they had no intention of developing in the biotechnology segment.

One last example was the need for a somewhat rare metal salt associated with a purification step that did not have an established specification. As a result, the level of purity sought was extreme, leading to the development of an expensive manufacturing process and minimum order requirements that exceeded near-term requirements. Ultimately, it was determined that the specification did not have to be so stringent. It was a very costly sequence that might have been avoided if the critical quality attributes had been determined earlier on. This becomes increasingly difficult in the field of complex biologics, due to understanding how the critical quality attributes affect the cell and gene therapy (CGT) product.

Could you elaborate on the Design for Supply model and how it contributes to a more resilient and effective therapeutic offering?

Many of us have first-hand experience with “clean-up actions” and hastily scrambling to get the necessary disciplines and compliance in place when product is moving through development and on the verge of late-stage clinical trials. Knowing that earlier engagement would drive more efficient utilization of resources and allow time to have everything in order argues for education on the overall organization of the supply chain and quality elements that will be required to realize the corporate goals.

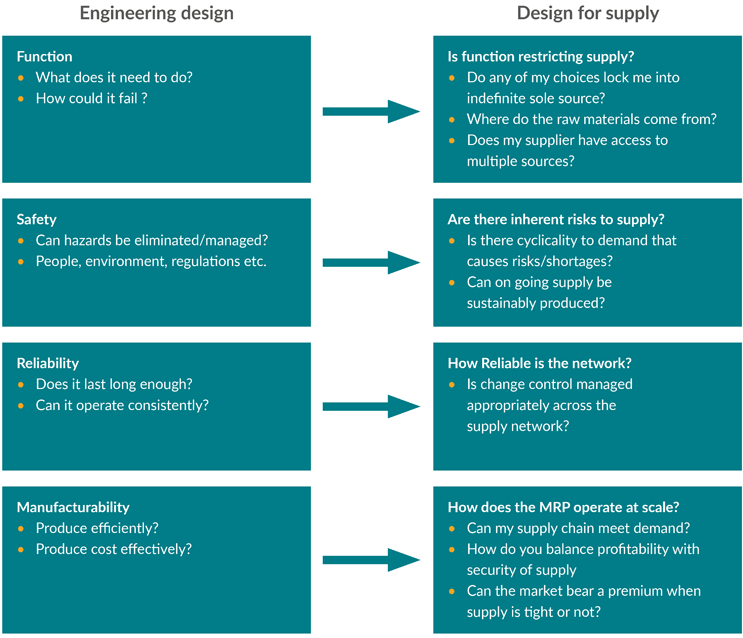

The Design for Supply model described above is not an alternative to the existing development model but rather a supplement to it. Recognizing that there is much more to getting a new therapeutic to market than just making it work in a preclinical model calls for expanding the list of critical steps to be taken and the execution of those steps earlier in the cycle. Our experience shows that by incorporating supply chain considerations into the scorecard for the selection of technologies and suppliers along with the quality by design characteristics, you can more readily weigh the trade-offs and prepare for or eliminate risks by looking at development and supply chain considerations holistically. By including the ultimate supply chain requirements in the development cycle, all facets of the business will be ready to launch when the product development phase nears completion.

How does the early consideration of supply chain disciplines help in risk mitigation?

Earlier identification of risk allows more time to mitigate and adapt efficiently instead of being in a strictly reactionary mode. Supply chain disciplines include identifying operational risks in future supply and developing a resilient infrastructure that includes risk transparency and an informed development of risk tolerance.

What strategies would you recommend for implementing these disciplines early in the product life cycle?

Employ an organizational model that includes supply chain disciplines earlier in the development cycle. This might look like one or more additional seats at the table or additional criteria for stage-gate advancement of a product in development. Getting the disciplines on the to-do list and assuring the skillsets are on hand to accomplish them can better align the organization for success.

How does this approach apply to other biopharmaceutical products beyond CGTs?

Some of the examples provided above are from non-CGT environments. Most biopharmaceuticals coming out of small or new firms are not developed using a holistic model. Speed and, often, cash constraints prevail, but our recommendations apply to all biotechnology developments. CGT brings a heightened urgency because of its fast pace and the very difficult justification to introduce changes later when the volumes are so small. But again, many orphan drugs are not optimized from a supply chain standpoint because of the cost of later-stage changes.

What are the potential obstacles to implementing this approach and how can they be overcome?

Available skillsets may be an issue if the company is trying to grow with an initial labor profile that may be more science oriented. Executive management may also be financially myopic, not wanting to invest until there is more proof that there will be success. Ultimately, it is the absence of understanding the cost of a misaligned development process that may lead an organization to defer bringing the rest of the disciplines into play earlier on.

How does this approach balance the requirements of the development team with other functions?

It integrates the functions in the organization earlier on and educates that earlier investment is less costly if the product is to be successful. Everyone in the organization can learn the full set of requirements and work together to ensure products are successfully launched with robust, cost-effective supply chains.

The benefit of this approach is that it also enables suppliers and end users to work together to leverage new-to-world technologies without false starts. Developers of new technologies are striving to make enabling solutions to solve problems and for end users who want to implement cutting-edge technologies. From a process development side, those end users have the freedom to do that, balanced with a supply chain-centric look at stocking, deliveries, lead times, and capacity planning.

What impact do you see this approach having on the future of new therapy development and commercialization?

Beyond the immediate benefits to new product development, a longer-term benefit could be the evolution of more cross-functional organizations where employees are enriched by exposure and possible first-hand experience in the rest of the disciplines of the corporation. Consistent with the mantra of “quality is everybody’s job,” if the employee base embraces the challenges of all their colleagues, a remarkable culture can unfold, yielding many benefits.

Are there specific tools or methodologies that you recommend for integrating supply chain management into the early stages of product development?

From our perspective, where teams were most successful in anticipating and managing supply chains of new materials, the difference was when they included the list of future supply chain requirements earlier in the stage-gate documentation. This ensured that they were receiving the appropriate visibility and resources that could be aligned for the coordinated completion of the development cycle.

Mapping out the development in a manner consistent with mapping out the product development life cycle also provides necessary visibility and highlights gaps that the organization will need to address earlier on. It is important that there is a person or small group who is accountable for the supplier strategy regardless of whether this responsibility is their primary role. The key is to understand and clearly define the accountabilities/responsibilities so tasks are not overlooked.

Conclusion

This Q&A discussion illustrates the issues facing CGT developers and supply chain personnel while recognizing opportunities to work more closely together. Ensuring consistent high-quality drug product manufacturing under continually compressed timelines remains a significant challenge for developers, and ensuring the supply chain is prepared to support the growing industry is key. Continuing collaborative discussions between the development and supply chain teams will inevitably save time, reduce costs, and ensure the sustainability of manufacture of the product. Check out the recent BioPhorum paper on the topic, Navigating the cell and gene therapy supply chain: insights, practices, and distinctions.