Bringing CGT Home: Equipping Community Hospitals For The Next Frontier

By Adam Boyer, Lee Buckler, Quinn Civik, Alessia Deglincerti, Ph.D., Joe DePinto, Rahul Mirchandani, and Sanjay Srivastava, Ph.D.

Geographic and logistical barriers remain a critical challenge because CGTs are delivered at select tier 1 academic medical hospitals. Research shows that when patients must travel more than 50 miles, even with family support, they often opt for alternatives to CGT. Overcoming these barriers is a shared priority among providers, manufacturers, and advocacy groups. The most current data on qualified treatment centers is sourced from trusted organizations including the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy (ASGCT), the Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy (FACT), BMT Infonet, claims databases, and product-specific websites.

As cell therapy products evolve toward outpatient administration and broader use in community settings, several product-specific factors guide their suitability for decentralized delivery. These include but are not limited to:

- The target product profile and approved label

- The nature and timing of side effects

- Incidence of Grade 3/4 adverse events

- Feasibility of remote patient monitoring

- Established referral pathways to hospital sites equipped for ICU-level care, if needed

To advance the decentralized delivery of CGTs there are serval challenges the industry must overcome.

A Dose of Reality

While delivery of these therapies at community hospitals (non-federal acute care) could help alleviate patient access issues by establishing them as extensions of AMCs, they often lack certain requirements to do so. Because these centers are most often not included in the clinical studies of CGTs, these hospitals often need to learn how to safely administer complex CGT treatments, which require therapy-specific operations, general infrastructure they may not have, staff training, and compliance to regulatory requirements. To date, CGT developers have struggled to include community hospitals in their treatment network, citing three major hurdles. In this article, we will explore potential pathways for overcoming these access barriers and improve patient adoption to CGTs.

Clinical Capacity and Infrastructural Capabilities: Building the Right Foundation

Bringing CGTs into community hospitals isn’t as simple as stocking a new medication. These treatments require a full ecosystem, including specialty equipment, trained staff, and strict compliance to process protocols related to things like collecting patient cells, product labeling, maintaining chain of identity and custody, and keeping the cells viable until they can be infused. The infrastructure and training requirements for apheresis, cryopreservation, and preparation of the final product for infusion are all significantly burdensome. Whether hospitals build these capabilities themselves or team up with trusted partners, having the right setup is key to making CGTs safe, effective, and scalable in local care settings.

To bridge the gap, many community hospitals and clinics are turning to a “plug-and-play” approach. For example, the partnership between BCA and Galapagos NV, a biotech company working on autologous CAR-T therapies required to be manufactured locally to ensure that fresh cells are used whenever possible (with no cryopreservation). BCA’s network of 60+ apheresis centers and 15+ sites with ISO-7 clean rooms with strong ties to local hospitals across the U.S. helps Galapagos achieved a highly distributed model for collection and manufacturing of patient products which is local to the patient, their referring physician and their community hospital. In certain larger urban areas Galapagos has partnered with corporate CDMOs, such as Landmark Bio, Catalent, Moffitt Cancer Center, and Thermo Fisher Scientific, to help service large medical centers in their local region. Strong, flexible ecosystems are what makes it possible to deliver CGTs safely and efficiently.

1. Orchestration: Making the System Work in Sync

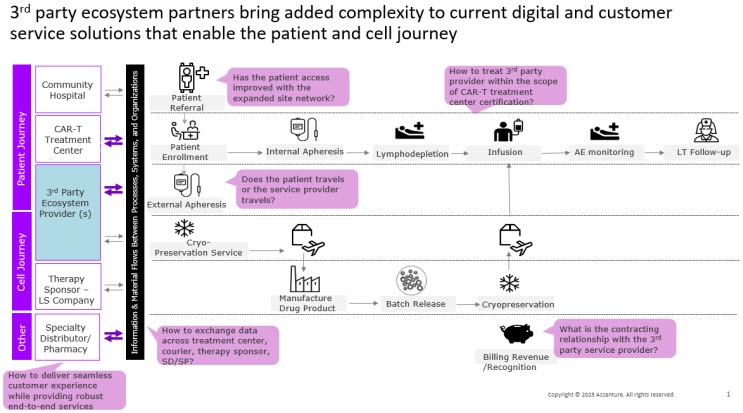

Working with a third-party provider for services like apheresis adds new layers of operational complexity (see Figure 1). It’s not just about handing off a task, it’s about making sure everything stays coordinated. Orchestration is the daily effort that keeps patients, products, and teams moving together on a tight schedule while ensuring compliance with product chain of identity and custody requirements. That means making sure the right people, places, products, and information are all aligned so the right patient gets the right therapy safely at the right time. It involves more than just booking appointments, it includes verifying a match of patient and product identity, being ready to escalate care if needed, sharing information smoothly across teams, and making sure payment steps don’t slow things down.

Figure 1. Adding a third-party ecosystem partner just-in-time patient and cell journey but unlocks significant available capacity to dramatically improve patient access.

What does this mean, practically?

- Site onboarding and workforce: As CGTs move beyond academic hubs and advanced medical centers, the role of the biopharma’s field team changes. They need to evolve from being just educators to supporting new sites in building the capability to deliver these therapies safely and in sync with others. In some instances, this may be done by the biopharma sponsors contracting directly with external players to provide support needed by the treatment centers. These teams must make sure all the players know their role, and everyone is on the same page. Onboarding isn’t just a checklist, it’s a full capability build of internal and external players that includes readiness assessments, closing gaps, cross-functional training, and dry runs before treating the first patient. There should be clear go or no-go criteria and if one partner isn’t ready, the whole site isn’t ready.

- Data and interoperability: For CGTs to work in a distributed model, data needs to move as smoothly as the therapy itself. Standardizing systems early and scaling from there helps reduce friction. But when electronic health records, portals, and communication tools don’t connect well, it creates room for error. Third-party partners maintain their own health information technology and quality management systems, which may not be interoperable or connected with the associated local community hospital. The absence of shared infrastructure and data interoperability may affect the customer experience of apheresis unit operations, including patient scheduling and treatment processes.

- Governance and safety: A network only works if it behaves like one program. The strength of this model comes from shared standards and faster learning. One set of SOPs. One on-call roster. One way to fix problems across all sites. However, there’s always a risk of drift. Protocols can slowly change, handoffs can rely too much on memory, and people can assume someone else is handling a task. Accreditations like AABB and FACT may slow the onboarding process, adding additional complexity to the process while mandating compliance beyond the standards in place. Strong governance keeps everything aligned and responsive.

- Patient experience: With the FDA’s elimination of Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) for CAR-Ts, there’s a timely opportunity to bring CGT treatments closer to patients. Delivering these therapies in the community—when done right—makes care more convenient by reducing travel and minimizing time away from home. The benefits are clear: patients stay local, caregivers maintain their routines, and follow-up visits are less disruptive. However, it also means more coordination is required between referring and treating physicians, the patient, and their care teams. Patients need one clear point of contact, easy-to-follow instructions, and reassurance that if something goes wrong, they’ll be admitted quickly to a trained site. Caregiver education and support should be part of the plan from the start, not something added later as a courtesy.

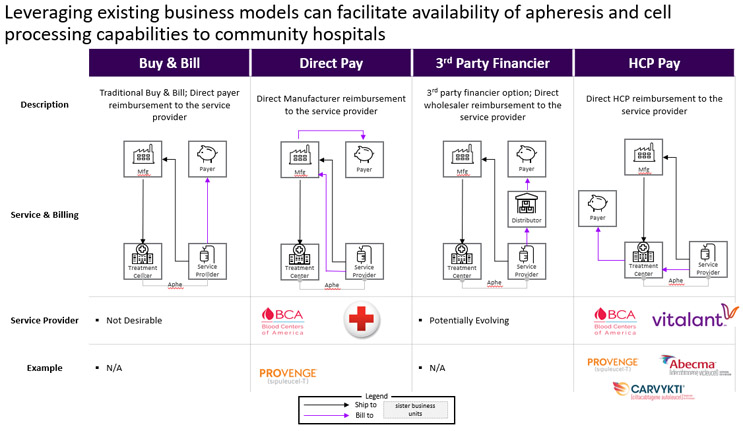

In vertically integrated hospitals, clinical trial sponsors take an active role in the patient journey. Many clinical trial sponsors build dedicated portals to help coordinate care more efficiently. Once the therapy needs to be scaled commercially, however, sponsors need new ways to address and share the burden of this orchestration. Particularly as community hospitals lean more on third-party providers, therapy sponsors face new responsibilities including the need to build digital infrastructure, negotiate business models, and establish agreements with both external suppliers and treatment centers to ensure the entire care process is covered. Digital and regulatory requirements vary in horizontally integrated centers depending on where products are manufactured and where cells are processed. Onboarding and certifying treatments sites must go beyond the facility itself to include the entire local ecosystem of providers playing an integral role in the product and treatment orchestration. Sponsors need to consider all ecosystem partners and take a comprehensive approach to preparing the network. This will often require the sponsors to have direct relationships with these partners rather than rely on the hospitals to manage these providers as subcontracting vendors. Figure 2 presents several potential business models which may be utilized to coordinate the different organizations involved in a patient's treatment journey:

- Direct Pay Model: Used in Dendreon’s PROVENGE®, this separates cell collection from treatment by the biopharmaceutical company contracting directly with apheresis centers. Sponsors gain direct oversight of quality and logistics while simplifying agreements.

- HCP Pay Model: Common in CAR-T today, this positions third-party providers as subcontractors to treatment centers, leaving reimbursement in the center’s hands but limiting sponsor visibility.

- Emerging Models: “Buy and Bill” and “Specialty Pharmacy” structures are still exploratory but could spread risk more evenly. Their adoption will depend on payer relationships, which most apheresis service providers do not currently have, and the ability to integrate into the CGT value chain.

Figure 2. Several business models can be used to coordinate the patient and financial flows between partners.

In the Direct Pay model, therapy sponsors treat third-party services as value-added partners. They contract these providers directly and manage them within a centralized quality framework. This approach gives sponsors greater control over their supply chain, logistics, quality standards, and accreditation, while also improving patient access to cell and gene therapies. In contrast, the HCP Pay model reflects current industry practice but represents a chokehold on supply chain expansion. Third-party providers are managed by treatment centers, which makes the process more seamless for therapy sponsors but limits their direct oversight.

To support these models at scale, the industry needs more capable digital infrastructure tailored to each product, supply chain, and business model. This infrastructure should enable efficient data exchange between entities and enhance the overall customer experience. In many cases, sponsors may operate multiple models at once, so it is important to design systems that avoid unnecessary complexity for any participants in the ecosystem and can ideally be used across cell therapy products provided by different biopharma sponsors.

2. Finances: Derisking the Model

As more CGTs move into outpatient settings, the cost of delivering these treatments continues to be a major challenge. Smaller community hospitals are already under financial strain, and the growing complexity of CGT is only making things harder. To make these hospitals a viable option for CGT delivery, the system needs to ease the financial pressure they face. With new CGT approvals coming more frequently, hospitals are seeing a stacking effect where multiple therapies impact budgets at the same time. This is pushing them to look for alternative ways to meet patient needs. One option is to work with specialty pharmacies to deliver CGTs through “white bagging,” where the hospital bills only for the services provided. There are several promising ways to reduce the financial risk and help hospitals build up their CGT capabilities. Since the cost burden is often more than even large hospitals can manage, it makes sense to bring in third-party partners like specialty pharmacies and, perhaps, wholesalers. These partners can help absorb some of the financial risk and support reimbursement efforts with health payers.

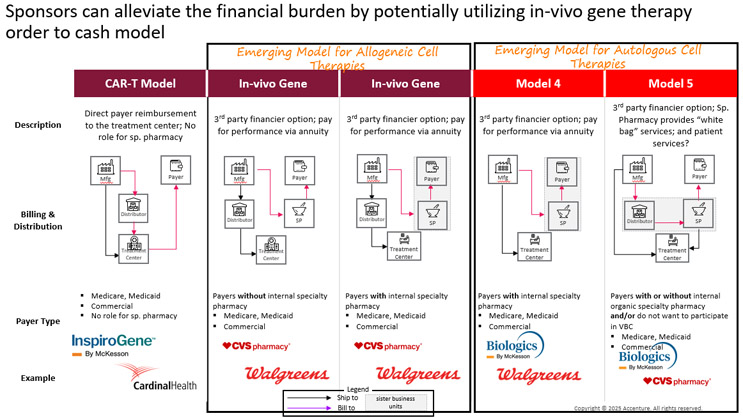

Figure 3 outlines several reimbursement and distribution models where specialty pharmacies and wholesale distributors could help ease the load:

Figure 3. Specialty pharmacies have the potential to ease financial risk by transforming reimbursement and distribution models. Please note that this set of Service Provider examples is non-exhaustive.

One of the biggest challenges with high-cost CGTs is the upfront payment required from treatment centers. If reimbursement from payers falls through, the center absorbs the loss. With the expected growth of allogeneic therapies and rising patient volumes, even large hospitals may hesitate to take on that kind of risk.

In the case of CAR-T therapies, specialty pharmacies are not currently involved, so the financial risk falls entirely on the treatment centers. However, there is a clear opportunity for third-party players to step in and help, especially if the right financial incentives are in place. Outside of CAR-Ts, specialty pharmacies are already starting to take on more of this risk, either independently or in partnership with distributors. For example, Biologics by McKesson is currently supporting Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) therapy at Iovance Biotherapeutics. As CAR-T therapies expand into smaller hospitals that are less equipped to carry financial risk, it will be essential to rethink how payment flows, and risk-sharing are structured.

Conclusion

Decentralizing the delivery of CGTs to community hospitals presents a valuable opportunity to improve patient access, but it comes with significant challenges. These hospitals often lack the infrastructure, trained personnel, and coordination systems needed to safely administer complex therapies. Partnerships with third-party providers such as blood centers and CDMOs can help fill these gaps by offering specialized capabilities for cell collection, processing, and logistics. Success depends on strong coordination across the care continuum, including data interoperability, standardized protocols, and clear governance to ensure safety and efficiency.

Financial sustainability is also a major concern. The high upfront costs and reimbursement delays associated with CGTs make it difficult for smaller hospitals to participate. New business models such as direct pay arrangements, specialty pharmacy involvement, and hybrid risk-sharing structures can help distribute financial burden and improve payer engagement. Therapy sponsors must take an active role in building digital infrastructure, managing third-party relationships, and designing scalable systems that support multiple therapies. By aligning clinical readiness with operational and financial innovation, the industry can make CGTs more accessible and bring transformative treatments closer to patients in their own communities.

References

- Andrea P Chung 1,∗, Jason T Shafrin 2, Sachin Vadgama, et.al. “Inequalities in CAR T-cell therapy access for US patients with relapsed/refractory DLBCL: a SEER-Medicare data analysis” Blood Adv. 2025 May 20;9(18):4727–4735.

- https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/approved-cellular-and-gene-therapy-products

- https://www.evernorth.com/articles/the-history-and-future-of-gene-therapy