Pioneering The First Cell Therapy For Solid Tumors

By Tyler Menichiello, Chief Editor, Bioprocess Online

Back in February, the FDA approved the first cell therapy for solid tumors — Iovance Biotherapeutics’ Amtagvi (lifileucel). Amtagvi is an autologous T-cell therapy — or more specifically, a tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy (the first TIL therapy to be approved by the FDA) — for patients with previously treated, unresectable or metastatic melanoma. To learn more about this first-in-class TIL therapy, I met with Iovance’s chief operations officer, Dr. Igor Bilinsky, Ph.D., and chief medical officer, Dr. Friedrich Graf Finckenstein, MD. They explained what sets TILs apart from its other T-cell therapy counterparts and told me about Iovance’s preparation leading up to this monumental approval.

A Polyclonal Approach To Oncology

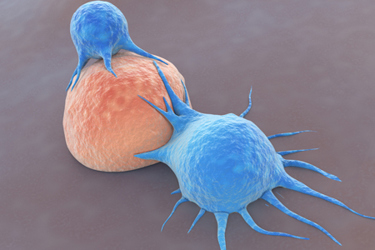

Though they’re both autologous T-cell therapies, “there’s a big difference between TIL and CAR-T,” Bilinsky tells me. Traditional CAR-T cells are engineered to target a single antigen (most commonly, CD19 or BCMA), whereas TILs are polyclonal, meaning they can target multiple antigens. “Solid tumors are generally more complex than hematological tumors in that they’re driven by multiple mutations, not a single mutation” he explains.

Another key difference between CAR-T cells and TILs is how they’re manufactured. CAR-T cells are made by genetically engineering a patient’s T cells to target CD19 or BCMA. TILs, on the other hand, are not genetically modified — they are isolated from a patient’s resected tumor and expanded over the course of a 22-day process before being infused back into the patient. “We’re basically taking the T cells that sit in the tumor and regrowing them up to the billions of cells,” Finckenstein explains. “And because we’re removing these cells from the tumor microenvironment, we are, in a way, rejuvenating and reactivating them by letting them grow outside of the body and outside of the tumor, which is immunosuppressive.”

The clinical promise of TILs goes back decades to the early work of Dr. Steven Rosenberg, MD, Ph.D., who first explored their efficacy in melanoma patients in 1988. Bilinsky says this early clinical data, along with the significantly unmet need of patients with metastatic melanoma, are the reasons behind Amtagvi’s lead indication. However, both Bilinsky and Finckenstein believe that TILs can effectively treat a whole host of solid tumor cancers, not just melanoma. Finckenstein says, “making this therapy accessible to patients with advanced melanoma is just the start.” They tell me the company is already exploring TIL efficacy in non-small lung cancer and cervical cancer with ongoing clinical trials.

Scaling Manufacturing To A Commercial Scale

Even though they were first used in patients more than 30 years ago, Iovance is the first company that set out to commercialize TILs as an approved cell therapy. “The big challenge was taking the step out of this academic clinical trial concept and making this therapy into something you can actually provide to a broader set of patients as a prescribable medicine,” Finckenstein says. Bilinsky tips his hat to the early pioneers of CAR-T who laid the groundwork for commercial cell therapies. “We are standing on the shoulders of giants, so to speak,” he says, “as we’re developing cell therapy for solid tumors based on the experience of cell therapies for hematological malignancies.”

Bilinsky and Finckenstein say the first step towards commercial approval was to standardize the manufacturing process and shorten it from six weeks to 22 days. The company also had to modify the process to result in a product that could be cryopreserved. “Up until Iovance picked up this technology and optimized it, patients had to actually go to the academic institutions where the TILs were made,” Finckenstein tells me. “These cells were not frozen, so as soon as they were done, they had to be administered, which meant that patients had to go back to get their treatment.”

Iovance had to work closely with the FDA as it refined its novel manufacturing process. Bilinsky says a lot of work was done with the FDA over the past several years to develop potency assays and novel analytical methods, which was just as much of a learning experience for the FDA as it was for Iovance. “The major learning here is to work closely with the FDA; help them educate themselves and work through the process to get a timely approval,” he tells me.

Building A Manufacturing Facility

Bilinsky says building a manufacturing facility specifically designed for TIL production was an integral part of preparing for this approval. “We built our own facility to ensure that the process is reproducible and very well controlled,” Bilinsky says. “We believe it’s the core capability for a company like ours to control the manufacturing process.”

Iovance built its 136,000 square-foot facility — the Iovance Cell Therapy Center (iCTC) — in Philadelphia, with an initial investment of about $85 million. According to Bilinsky, this location was chosen for several reasons:

- The proximity to major academic centers and the abundance of manufacturing talent in the area.

- The proximity to the airport, which allows Iovance to serve patients in both the U.S. and Europe.

- And, perhaps not surprisingly, because it’s more affordable to erect a big manufacturing center in Pennsylvania than somewhere on the West Coast.

“Now that we’ve built and commissioned the facility, all of these reasons are playing out exactly as we’d hoped,” he tells me. He attributes the successful construction and design of the facility to members of his team who brought experience with them from building manufacturing facilities for autologous cell therapies.

When asked about advice he can offer his peers (i.e., companies thinking of internalizing manufacturing and even building a facility to do so), Bilinsky says, “one needs to balance external manufacturing with internal manufacturing; it has its pros and cons.” The biggest pro is the control over the facility and quality control of the process and product. The con, he says, is that you need to invest significant capital to make it happen. “Part of it is just making sure you have access to capital to make it happen, and it’ll pay off later down the road.”